TRIP #3 DAY 4 JOURNAL

A few things have changed since I left a week ago. First, every patient who was in the ICU when I left has died between then and my return. Second, a lot of the contract staff is also gone. I was perplexed as to why they were laying off most of the contract staff but asked me to stay on through July if I was willing. I asked around, and the regular staff said administration asked them which contractors they wanted to keep for longer and who they felt were the most helpful. They kept those staff and have axed most of the rest. I made the cut, apparently, probably in small part because they can bounce me back to emergency services if a second surge happens during my contracts.

I’m pretty disappointed that a few of the patients from last week died. I had been particularly hopeful that one, the Muslim man in his 40s, still had a chance. I was expecting the rest of the patients in the department to die, and I suppose I expected him to as well, but I was hopeful nonetheless. I had extubated him and he did okay off the ventilator for about two days until he had to be reintubated. He was even responsive and able to communicate with us. I was hesitantly optimistic he would pull through. The current batch of patients aren’t much better off than those from last week. Our death rate has decreased a bit; half of the ICU is currently non-COVID patients. Some of them are non-COVID surgical cases that just need a day or two of ICU care due to the complexity of the surgery itself. Their prognosis is significantly better than most of the non-surgical cases. We’re only averaging one or two deaths per day now, as opposed to two to three when all 14 beds were COVID patients.

I always used to get a little adrenaline rush when a patient tried to die during my shift. My training was really centered around life-sustaining medical management, as that’s what emergency services is really there for, and it used to be exciting when I actually got to use that training. It was a useful rush, one that I had learned over time to focus toward what needed to be done but one that for the uninitiated can be panic-inducing or impair judgment. I’ve lost that rush entirely, and the prospect of a patient trying to die has become no more adrenaline-inducing than writing a medical record note. Every night we’ve had at least one or two patients try to die (and a couple who succeeded). Their heart rates or oxygen levels dropped, or they deteriorated in some other way, and the stress that comes with that situation is just not there anymore. It’s more like “Oh, they’re trying to die again. I guess I have to fix that.” The lack of adrenaline hasn’t impacted my ability to do what needs to be done, but it struck me as odd to feel the same way about dragging someone back from the pearly gates as I do updating the sign-out report we give to the next shift.

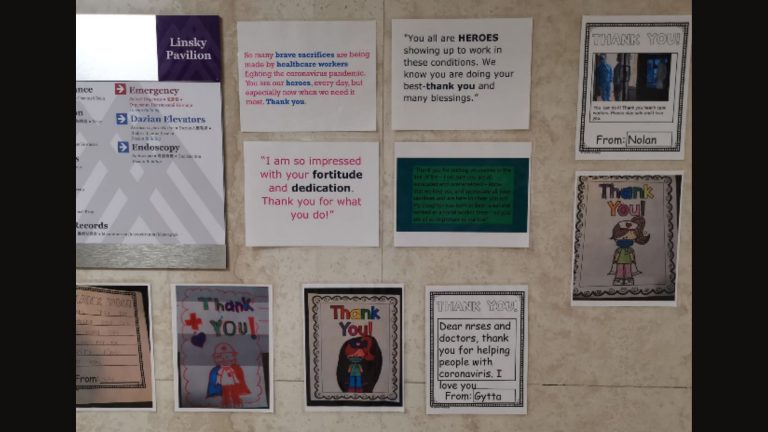

Some of the nurses have mentioned how exhausted they are. They’re all seasoned ICU nurses, but even they’re not used to this much death. The burnout is really showing, and at a certain point no amount of expressed support, 7pm public ovations, free meal deliveries, or hazard pay makes up for the stress of extremely sick patients and risk of disease exposure to themselves. I still can’t help but feel sorry for their situation. It’s hard to be told you’re a superhero when the reality is we’re just not saving many people here.

The juxtaposition between the reality of our situation and the public’s insistence that we’re heroes is just staggering to try to contend with. I found a scholarly article on Superman comics during the Vietnam war (which, funnily enough, cites one of my undergraduate professors, Dr. Chris York, who did a similar dissertation on Batman comics and popular culture). During Vietnam, the Superman comics went through an arc in which Superman had part of his power siphoned away by a villain and had to contend with having lesser powers than his previous normal. Part of the story is Superman learning to contend with his own perceived insufficiency. He goes briefly mad and harms a few innocents in his attempt to compensate for his shortcomings. Superman does ultimately defeat the villain who took his power and has the opportunity to have it restored. He declines restoration, declaring he has seen the consequences of excessive power and opted to stay in his weaker state. Right now, I feel like I’m in the insufficiency stage of a similar process, and I’m not sure there is a way to progress out of that stage other than coming to terms with my limitations. It’s hard not to go mad when my deficits stare me in the face with every patient deterioration death, even though mine are the same as everyone else’s. Maybe I am luckier than I realized not to feel anything about it all.

JACKIE CHRISTIANSON

Author

Share this post

Nurses International is a non-profit entirely focused on helping nurses obtain the education and the support they need to make a difference in developing nations worldwide.

We connect colleges and institutions with experts who can take their nursing programs to the next level. We help establish new nursing programs where they’re needed most. And we eliminate the barriers that stand between students and education.

QUICK LINKS

CONTACT US

FOLLOW US

EIN: 46-4502500